Richard M. Wheelock, "Intratribal Cooperation and Communications: Is Consensus Possible?"

©April 12, 2017

Abstract:This paper will draw upon scholarship in Indigenous Studies and the experiences of the author in considering the serious challenges of fracturing of tribal identities and communities after generations of economic, social, cultural and political crises brought on by global colonial forces.(1) In seeking creative responses based upon timeless tribal conceptualizations, and in forging strong principles of group cohesion for the future, tribal nations are forced to consider how they may balance the forces of seemingly stark individualism of the mass society that surrounds them with those of cooperative tribal values that have proven resilient over the generations. In the precarious arena of tribal self-determination, support among tribal members for cohesive approaches to unpredictable challenges to their own peoplehood remains the basis for tribal survival into the future.

In 1984, the famed Vine Deloria, Jr., in a book he co-authored with Clifford Lytle, pointed out that few tribal communities can be as cohesive as those that once existed before contact with European colonizers. He was also quick to point out that appeals to tribal religious traditions sometimes run counter to the current experience of Native people within today's tribal communities, since so many have been influenced by Christian and even other spiritual traditions for many generations.(2) Finally, he was careful to note that in most tribal traditional form of government, "...most Indian groups did note exceed several hundred people, and a good deal were less than a hundred people."(3) His observations remind us that when we consider the current, often chaotic atmosphere of internal debates over policy issues within tribal communities, we must remember to factor in generations of change in tribal governance. We must also consider the experiences of generations of our tribal members with colonization and human adaptation as we look for solutions to the sometimes discouraging and divisive nature of internal dialogue in tribal governance. For those tribal nations who have maintained a common identity as "Unkwe hu weh, Onu yote a'ka, Haudenosaunee" or as people carrying on the transformed and continuously adapting identities of their People, though, the challenges of finding ways to improve the processes of reaching consensus, or at least finding common purpose as tribal citizens, can probably best be framed within the idea of their continued shared peoplehood.(4) That challenge of finding some common ground for serving the common good in tribal internal policy-making in times of continued rapid change is the one this paper will focus upon.

I believe it is crucial that in such a discussion as this, that individuals maintain a clear sense of one's own position in supporting her/his nation's peoplehood. The author of this paper, for instance, must remain aware of his own experiences and his own limitations in maintaining not only "citizenship" in the Oneida Nation in Wisconsin, but his understanding of the evolving nature of the self-concepts and tribal identity of other members of the Oneida community. For me, as a half-blood, off-reservation person with only a few years' experience in living within the exterior boundaries of the Oneida Reservation, the chances for significantly improving the atmosphere of internal debate seem slight. Yet as has our traditions tell us, important contributions can be conveyed by people who would seem to have little opportunity or desire to become great tribal leaders. My long education in indigenous studies and my work as in higher education, coupled with my brief, sporadic, but significant personal experience within the community, provide some compelling determination within me to continue my personal struggle to discover ways to contribute what I can to strengthening Oneida's quest to remain a people in the maelstrom of today's broad political and intercultural world.

Beyond the long story of our Oneida side of the family, I often cite my teaching experience beginning with the very first year of the Oneida Tribal School, the Onu uh yote aka tsi tu wah dili hun ya nit' ha, in 1979. I also worked as editor of our tribe's newspaper, the Kalihwisaks for several years before leaving the community again to begin my graduate school education. That graduate school portion of my knowledge quest was preceded by my undergraduate studies at Fort Lewis College, where I would eventually return to teach for nearly 30 years, ending with my retirement in 2013.As of the writing of this paper, I am a two-year volunteer review editor of the Indigenous Policy Journal, an emerging media voice in the now global dialogues about the continuance and strengthening of indigenous peoples. I often provide this thumbnail sketch of my personal "stake" in the survival of our tribe because it speaks of the variety of backgrounds people bring to the struggle for cohesion in our now diverse and sometimes fragmented tribal community.

But there is more to a person's background that formulates one's perception of things. One's career experiences reveal some interesting clues for finding both the supportive environment and the mutual support of peers in overcoming debilitating colonization. In the 1970's, for instance, this author was involved as coordinator in creating a public school Indian education program in Oregon, using the complex tool of an advisory board of intertribal people, including some Native parents, administrators and teachers in concert with non-Indians of similar social and professional standing. I've already mentioned working briefly as a teacher within the high-morale community surrounding the creation of the Oneida Tribal School in the later 1970's. Then, in the 1980's I experienced the art of local journalism as a community-building function for the tribe as editor of the Kalihwisaks, the tribal newspaper I have also mentioned above. I then began my graduate studies in the mid-1980's at the University of Arizona's MA program in American Indian Studies, meeting peers and an unusually influential Native faculty in the environment of high expectations in one of the nation's premier university settings. For the students in the American Indian Studies program at that time, it was a chance to meet and study with the likes of Vine Deloria, Jr., Robert K. Thomas and Tom Holm.

The graduate experience for me was extended some years later in the 1990's at the University of New Mexico, as I eventually received my PhD in American Studies, being forced in the long effort to produce a dissertation to synthesize much of the experience and scholarship I had received by then in Indian country. My dissertation was entitled "Indian Self-Determination: Implications for Tribal Communications Policies." Finally, my faculty career at Fort Lewis College that ended in 2013 gave me the opportunity to work closely with Native American students of many tribes at a college where a tuition-waiver assured that a sufficient number of Native students from throughout the West and elsewhere would attend my classes in Native American and Indigenous Studies, which I had the pleasure to coordinate during its creation. NAIS became a Bachelor's Degree-granting department at Fort Lewis College in 2011 after several years of concerted efforts by an advisory board consisting of staff, faculty, students of Fort Lewis College and higher education professionals from the Jicarilla Apache, Southern Ute and Navajo Nations. It was another experience in working with inspired people to create what we all hoped will always be a unique opportunity for students interested in tribal self-determination.

From all that experience working toward a common goal in self-determination and scholarship aimed at the same goals, it has occurred to me lately that some surprising dynamics emerged when people came together, shared empowering goals and achieved outstanding success. I believe there is substantial evidence here that the shared sense of working for a "common good" is a powerful part of human nature, one that lives almost as an entity of itself, striving to survive as would any being. Once it feels the surge of its members' efforts, as a body feels the surge of energy in its motions, the impetus for the common good can produce amazing results, beyond those intended or even imagined by people designing programs that brought the people together in the first place. One can tell when that process had been successful when the sense of peoplehood continues after the supposed leaders move on. I've even seen that unity of purpose among a local population continue when the programs that brought the people together have ended. I suppose many people who worked successful projects during the heady early years of the Self-Determination policy could tell similar stories.

There are, of course, both positive and negative outcomes of our experiences with overcoming elements of colonialism in our careers and experiences since the 1970's, and of our personal, limited understandings of the tribal traditions and identity we hope can provide a bridge to cohesiveness among us today. Not everyone in Indian country had such heady experiences as I've described above. Poverty, alcohol and drug abuse, diabetes and other maladies still haunt our communities, both in reservation and in intertribal urban communities. And, in many communities, we seem to have lost the capacity for reasoned, well-informed debate on the issues we face as self-governing peoples. Yet I believe it is clear from my own experience that it may be useful to consider the problems of finding effective dialogue among tribal members as a "communications problem," one that demands that we consider and even honor the actual dimensions of the tribal community, in both its positive and negative aspects. Such an analysis requires a demographic analysis in a deep, experiential sense. It seems we need to look deeply and with empathy, given the impacts of colonialism and continued social crisis, at how and why some of our people seem to periodically act out rage and frustration by blindly attacking their own tribal government without first checking the available facts in an issue. Of course, we also need to continue to seek the kinds of experience among us that can help resolve the factors that contribute to the continuing crisis of alienated tribal members as we take on the complexity of tribal sovereignty. Tribal nations still face consequences of intergenerational trauma,(5) consequences we seem to experience when broad, inclusive processes of decision-making are attempted in tribal communities today.

In crucial debates on policies that require expedient decision-making, we live with those consequences. They seem to arise when we become impatient with our own people and suddenly express our personal, deeply held, yet unexplainable frustration during debate among others similarly saddled with personal trauma. It is then that we speak from the personal frustration of generations of poverty, family breakdown and generalized feelings of isolation and hostility. These intergenerational consequences of powerlessness that accompany colonial oppression cannot be easily overcome just because we hope they will be. To move beyond them takes personal confidence and a willingness to tolerate compromise, virtues and skills not easily awakened even in those who believe they have become successful economically or socially, since those successes have often come in another arena, that of outside society, not within one's own tribal nation. That is changing in Oneida as it is elsewhere. Successes of many kinds in the Self-Determination era has offered new hope, especially when the revitalization of traditional activities help to reorient people to the common good. For some, reciprocal systems of trust seem to be emerging even as others continue to feel left out of the economic benefits of tribal self-determination. It seems the tools for solving our internal crisis are poised. What is needed is wide participation and commitment among tribal members to tribal identity beyond the simple demands for services. Let us see how we might marshal our tools for the task of community development in the positive sense of seeking the common good. But first, let's look at our adversary, the exclusively individualist, self-seeking spirit that divides our efforts.

Tribal survival today, it would seem, requires tribal members to consider the natural and human forces that brought them together in the first place. While one could consider many factors in such an analysis, one helpful model of tribalism continues to provide some useful food for thought in framing the question of what tribal peoples, in all their incredible variety, share as organizing principles of community. A model developed by Robert K. Thomas, whom I met in his classes at the University of Arizona, has always helped this writer think deeply about how our tribal ancestors saw the world around them in terms of their relationships and assumptions about the proper way to live an ethical life. I will only develop a few of the five elements of that model here, but the entire model can be utilized when needed for other discussions beyond this one about finding ways to improve internal dialogues. I have used this model in my classes and in many of my writings, so I apologize if the reader has heard this before. Here is the five-element model of pre-contact tribalism, almost entirely as I reiterated it in my dissertation in 1995:

1. Kinship structuring of the society: Practically all community activities rely upon kinship organization. "Institutions" are almost entirely made up of relatives taking personal responsibility for the tending of social obligations. A person's status in the community is a function of one's maturity and standing as a relative, in addition to, or even in spite of, one's achievements.

2. A sacred, oral tradition: Instructions and ceremonies are "given" at the time of creation, defining the People's responsibilities and place in the cosmos. Participation by both clan and individual is a major ethic in maintaining the proper balances among humans and with other beings. Relationships of respect are defined and the people's responsibilities in maintain those relationships are defined. Violations of the proper behaviors can bring about dire consequences, often in the form of illness or other suffering of the individual or among one's kinfolk.

3. A sacred society: Oral tradition also provides instruction for fulfilling the responsibilities within the communities of humans. A person learns the respect necessary for living in harmony with community members from kinfolk in an oral, face-to-face environment. Again, violation of the respectful relationships can bring on dire consequences. Both the participation in ceremonies and the meeting of kinship obligations are necessary to maintain the sacred order of things. Social controls include teasing, shame and, in severe cases, ostracism.

4. Responsiveness to the natural environment: There are many living, conscious "beings" in the natural environment, each requiring proper respect so that mutually beneficial relationships may continue. Omens and signs from the natural world are taken seriously, often requiring specific human actin to maintain balanced relationships. Ceremonies and other recognition of sacred places cement those relationships. The People have a sacred homeland, where they will fare well. Specific places carry special, sacred significance, as places of devotion, prayer and sacrifice for individual and community renewal.

5. A closed and bounded society: Since individuals are defined largely by the obligations to relatives, membership and participation in the group is necessary. "New" members must be adopted into the kinship structure so that order and structure can be maintained.(6)

This remarkable model is important background for any indigenous person who hopes to understand the conflicts their ancestors faced in assimilation programs and those conflicts that still exist in modern tribal nations today. This model is especially helpful if the reader compares elements of this model with one of the "mass society" that has imposed its lifestyle upon the peoples of the world via colonial and neo-colonial and now, neo-liberal economic policies still faced by indigenous peoples. Here is a model of that mass society, intentionally condensed into five elements for easier comparison to the model Thomas provides:

1. Bureaucratic structuring of the society: Since this is a large, intercultural society, the distribution of services, opportunities and responsibilities cannot be accomplished via a kinship system. A less personal organization is required and people are ranked as individuals in categories or roles in order to gain fair shares of the goods and services mass society provides. Corporations greatly spread the system of bureaucracy to many areas of human interaction.

2. Traditions subordinated to innovation: Mass society greatly values innovation, frequently ignoring even Western concepts of sacredness in the interest of efficiency and progress. Traditional wisdom is deemed far less important, since it is often considered obsolete. The manifest power of human technology leads to a more anthropocentric relationship with the cosmos. Literacy and electronic media of information dominate thought patterns, providing a greatly expanded system of telecommunications at the expense of face-to-face conversations.

3. An impersonal society governed by laws passed by humans: Society is seen as a secular process. One's responsibilities to other humans often requires formal law, since individuals must cooperate with many strangers daily. Neighbors rarely need to interact and even relationships within nuclear families are partially superseded by bureaucratic agencies as children spend their days in schools and adults take on work and career roles. Individuals are frequently anonymous as they pass through many "public" places.

4. Nature seen as controlled by humans: Objective and mechanical theories about natural process dominate. Real estate value of lands and "resources" displace most sacred values involved. Easy transportation and interchangeability of personnel qualified for specific categories of labor lead to a highly mobile portion of the mass society, reducing ties to specific homelands. Few people are directly involved in the now bureaucratic food production process, further reducing human interaction with natural processes.

5. An "open society": People can become "residents" simply by moving to a locale and living there for a specific, legally defined length of time. Insistence upon "civil rights" for each individual is an important basis of social interaction, reducing the need for membership in a geographically defined community. Other types of groups, based upon similar interests and backgrounds are important. As Lowery and De Fleur note, solidarity among these groups is difficult to achieve because of "...social differentiation, impersonality and distrust due to psychological alienation, the breakdown of meaningful social ties, and increasing anomie among members."(7)

These models of tribal and mass societies are offered here as a basis for the analysis of the roots of conflicts among tribal members today. The continued demands of the mass society that surrounds originally tribal peoples are part of the reason that people involved in internal debates crucial to tribal continuance face frequently unrecognized problems in basic communications. When they base their arguments in essential values of their shared cultural identity, for instance, both the speaker and the listener must bridge the gaps between understandings rooted in entirely different social and legal paradigms. In Oneida, as the history of the tribe reveals, assimilation policies and the nearby urban mass society of Wisconsin complicate conversations and behavior expectations to a relatively major degree. Of course, Oneidas have adapted to those conflicts in many ways, but as tribal governance demands expedient action to the timelines required in a mass society, the time and energy needed to decode and recode communications between individuals can become overwhelming if tribal people aren't aware of the problems the continued interaction between these two paradigms create. With the two paradigms in mind, we can consider the pressing need for effective internal conversations and communications on the issues tribes face.

As indigenous peoples work together to maintain their sovereignty and to serve the needs of their communities in the Self-Determination era, some troubling challenges persist that force them to consider how they can act with unity to maintain their sovereignty. Their efforts in economic development, for instance, are under constant attack from outsiders. In Oneida, Wisconsin, for instance, a long-standing challenge to tribal existence continues in the form of on-going challenges to practically any tribal action, even social gatherings, by the Town of Hobart, a township of the State of Wisconsin, created within tribal boundaries during the Allotment Policy during the early 1900's. That township attempts to exert its jurisdiction over tribal lands and tribal members at every opportunity. With its connections to an organization called Citizens Equal Rights Alliance (CERA) which lobbies for termination of tribal sovereignty, the township's almost daily incursions over tribal authority are irritating in the extreme, yet the real challenge tribes like the Oneidas of Wisconsin faces is not the continual court cases brought on by such non-Native forces, but their relative inability to successfully debate issues that might help demonstrate the responsible exercise of tribal sovereignty that would quickly disprove many the arguments of anti-tribal sovereignty organizations by doing so. Intratribal, internal struggles among tribal members over the direction of tribal policies and distribution of "benefits" instead are the focus of many interminable tribal debates. As is evident in many tribes, the body politic of indigenous nations in the United States continue to experience a kind of life-threatening lack of internal cohesion when unified decision-making seems most crucial. Since the recent U.S national and state elections, an even more uncertain political climate emanates from U.S. governing systems.

The crisis today is most evident among members of the Oneida General Tribal Council, defined as all tribal members of voting age, as constant bickering continues over per capita distributions and tribally-operated economic ventures. The tribal employment arena, too, has presented some alarming controversy as a number of tribal employees resist work discipline processes carefully crafted for the many tribal human services jobs and even in tribal business venture careers. Though the tribal Business Committee has worked diligently with its work force agency to assure fairness in employment, frequent cases concerning workplace tensions are reported in the tribe's bi-weekly newspaper, the Kalihwisaks. The woes of self-determination, one might say, seem to have become almost overwhelming at times.

Another example of this lack of cohesion in Oneida is that disaffected tribal members of the Oneidas of Wisconsin exhibit a discouraging level of obstinacy at General Tribal Council meetings that is expressed as disrespect for policies and people with which they disagree, including their own elected officials. They seem to be both consciously resistant to what they see as lack of transparency in government, unfairness in distribution of benefits and abuse of power among tribal officials and administrators. Their actions at times seem to indicate that they have grown resistant to authority in a generalized way, which some attribute to generations of oppression, neglect and poverty. Since stipends are paid to tribal members for attending these GTC meetings, some opine that it is in the interest of this minority of tribal members to petition for as many meetings as possible, then vote for a time limit on meetings, where they delay discussions with many unrelated comments and call for many amendments to any resolution, thereby forcing another meeting to be scheduled to complete the agenda. There, they expect to again collect stipends. Since a normal meeting of the GTC can attract nearly 2,000 members, the cost to tribal coffers is substantial. Clearly, they have mastered the process of petitioning for meetings of the GTC, processes that were enacted with the high ideal of empowering a traditional tribal value of direct democracy. Those not involved with this method of expensive obstructionism know that they must attend these tedious meetings, lest the obstructionists gain a majority in open voting on often damaging resolutions the obstructionists propose. Meanwhile, crucial issues and the constitutional duties of the General Tribal Council languish.

Despite a long history of oppression and resulting community divisiveness, the ingredients of cooperative, mutually supportive movements have emerged over the generations, sometimes without much fanfare and even surreptitiously and in the nick of time, as was the case during the throes of military-style colonialism experienced by our ancestors. Those movements of self-generating peoplehood have been targeted almost in a cyclic fashion by the entity that is colonialism, itself seemingly embedded within the complex federal policies resulting from neo-colonialism's continuing destructive tendencies. The results have left us with tribal lands and waters and scarred social relationships, relationships that our enemies continue to attack in the many termination and assimilation forces we still deal with across Indian country. It is easy to see why metaphors in myth and prophesy have arisen to describe the struggles between peoplehood and colonialism! It is an on-going story whose roots need to be considered in any analysis of today's crisis in internal dialogue among tribal peoples.

Interestingly, some possible solutions to today's crisis arise from the historical crises such as those the Oneida Nation in Wisconsin has experienced over the generations. That story may provide some insights into ways the tribal nation has survived, if researchers can discover the strategies each generation employed as they overcame the threat the policies posed to tribal identity. That means refocusing historical studies through the lens of tribal survivals and from the perspective of the Oneida people themselves, when necessary. Of course, several historical studies already have that focus, such as The Oneida Experience: Two Perspectives.(8) The historical responses of unity among tribal members in the face of crisis illustrate some unique capacities of the Oneida community, seemingly forged from intergenerational experiences gained from continual challenges to its existence over the years. As the tribal nation matures under the Self-Determination policy, the strength of Oneida identity among its membership in times of stress remain its salvation. The following are some examples of threats and some of the responses of the tribal nation over the years. Perhaps greater familiarity with the story of tribal survival since "contact" will bring today's Oneida people to consider strategies for greater unity as some inspirational and courageous tribal members took on the challenge to tribal identity in their times.

Appeals to our tribal identities as a call to action have often been used over our long history of resistance to colonialism. And we have risen to the challenge many times over many generations, as is the case in Oneida. With approximately 17,000 members today, the Oneida Nation in Wisconsin has survived the Removal Policy beginning before the 1830's, the Allotment Policy in the early 1900's, threats of Termination in the 1950's and, very recently, court challenges to its very existence as a legal entity. In contrast to those explicitly assimilationist and even genocidal policies, the Oneida people also experienced the Indian Reorganization Act Policies in the 1930's and the Self-Determination Act and its associated policies beginning in the 1970's. Since the Self-Determination policies began, the Oneida nation's dynamic members have rallied to create a tribal school, a tribal language program, agricultural businesses, a diverse economic portfolio based upon its successful gaming operation, and a wide range of services to its members. Tribal language programs and even the regeneration of the Long House religion among tribal members reveal a strong commitment to tribal identity as a basis of peoplehood for the Oneidas. At every step of the way, Oneidas have relied upon their shared identity to overcome divisions among themselves brought on by the elemental forces of colonialism at every turn. Divisions based upon religion, lost land allotments, even long-standing feuds between factions created as long ago as removal from the original homelands in what is now New York have somehow been bridged, sometimes temporarily, as tribal members resisted threats to their peoplehood. Many more divisive events and forces could be listed here, but the roots of factionalism are clearly deep and persistent, even when Oneidas sometimes find ways to succeed in their search for consensus today on specific issues.

Today's divisiveness seems unusually dangerous to tribal self-determination, though. Many members of the nation are now generations removed from life in the homelands in Wisconsin, scattered by allotment policies and the resulting poverty, which drove many to nearby cities and beyond. More recent economic and social opportunities, too, have attracted members away to even more distant job and career opportunities as the reservation economy continued to stagnate and local racism made social life difficult for Oneidas. Yet the community at Oneida often reached out to its distant family members, maintaining cultural ties despite the ensuing cultural shifts felt at many levels. Though the tribal language is among those considered threatened and for many years, the traditional ceremonies of the tribe were nearly absent, a truly Oneida identity has experienced a bit of a renaissance in the years since the Self-Determination policy began. The establishment of the Tribal Historian's office and the publishing of tribal historical and cultural materials reveal a strong impetus in the community for understanding tribe's story of survival.(9) Thus, the tribe has some powerful experience to draw upon as it now faces what might appear to outsiders as a debilitating crisis in its internal dialogues so crucial to survival in this era of tribal community development.

Conflicts between members and entities of the Business Committee and the General Tribal Council have resulted partially because of the nature of the tribe's constitution and by-laws, created in 1936. That constitution was forged amid considerable controversy, as with many tribes in that era. Yet the two governing bodies retain some interesting elements of governance from Oneida and Haudenosaunee traditions. That may not have been accidental, since the Bureau of Indian Affairs Commissioner at the time, John Collier, professed a kind of reverence for Native peoples and their social and political achievements. Collier stated many times that tribal traditions should be regenerated, if necessary, to become the basis for what were to become the new governmental institutions imposed under the Indian Reorganization Act of 1934. Collier was controversial in his approach, even among many Native people across the United States, partly because his proposals were necessarily rushed and because of the wide variety of situations the many tribal peoples faced at the time.

Whether the form of government chosen by the Oneida people under that law was intended to match aspects of Haudenosaunee and Oneida governance or not, the creation of the General Tribal Council as the ultimate authority in tribal governance mirrors pre-contact structures to a limited but important degree. In fact, one might consider at this point that in 1986, the US Congress recognized the Iroquois (Haudenosaunee) confederacy as the source for several elements of the US Constitution, which might lead today's Haudenosaunee and Oneida scholars to consider how mangled their model of governance had become by the time it was returned to them in the 1930's. At the time, though, the idea of reorganizing under the colonial version of governance offered under the IRA was controversial, though the take-it-or-leave-it conditions of negotiation under the IRA allowed little time for internal deliberations.

Though the 1936 constitution(10) wasn't perfect, it did offer an escape from the disaster that had been the Allotment Policy for the Oneidas. The IRA also empowered the tribe to manage its own small, federally-sponsored budget and allowed it to also direct its own New Deal programs for community regeneration and economic development experiences, most notably the Works Progress Administration program. Though the Termination Policy of the 1950's nearly undermined the nascent tribal government's small, but significant successes, a tribal oral history recording project begun by the Works Progress Administration in 1939,(11) provided a crucial record of tribal traditions and family histories. Several more cultural heritage projects continued the momentum of language preservation by producing Oneida language dictionaries and recorded oral versions of tribal lore by tribal elders who were still fluent in Oneida. That historical process has turned out to be a significant link to the traditions for Oneida people today, a link that clearly offers a key to solving the problems the nation faces.

Thus, two key elements of Oneida traditions survived those difficult times in Oneida history. In the transitions from the serious brush with cultural genocide under the Allotment Policy in the beginning in the late 1890's, to the determination to maintain the Oneida identity under the Reorganization Policy of the 1930's, to the reemergence of the threat of tribal atomization under the Termination Policy of the 1950's, Oneida generations can share the story of their own survival as a people in inspiring terms. It is easy to see in retrospect why the Tribal school, which emerged amidst the efforts of determined tribal members as the Self-Determination Policy reached Oneida in the 1970's, has been so vital for Oneida identity. Its curriculum was immediately built around those Oneida language materials and the surviving elders who could help convey them to tribal members. Tribal members have relied upon the preservation of portions of their culture from the Oneida oral histories; and they now had a governmental system that featured a form of direct democracy in the General Tribal Council, so vital to Haudenosaunee heritage,(12) which was again a priority for federal policy-makers, many of whom were Native people. In fact, Oneida people, like Robert L. Bennett and Ernest Stevens, Sr. were instrumental in the early stages of the Self-Determination Policy, working from different angles in Washington, DC. Their efforts to empower tribal nations show the character of rushed policy-making that seems endemic in Indian policy at the federal level, yet their clear intentions to get practical governmental processes that reflected at least some traditional concepts into operation for Native nations cannot be denied. It's difficult to imagine, in fact, the pressure to quickly establish key footholds for tribal sovereignty in terms Native people could understand and use in those times. Their stories, and the work of many Native people from many tribes in those days remain another source of inspiration, suitable for telling today as tribes forge ahead in pursuit of their own destinies as indigenous nations. Championing the struggles to establish beachheads of tribal sovereignty as a part of tribal history is an important strategy, since finding conceptual frameworks to rally people to a more unified position on the issues that confront them are crucial in these times of fractionalization and populist tendencies that seem to be widespread in Indian country.

Besides the devastating story of contradictory federal policies and their impacts and tribal internal struggles to survive, another conceptual frame one might employ in evaluating the forces that have created current chaotic and destructive dialogues among many tribal peoples is the idea of populism as a dynamic force that frequently arises in human populations. Again, populism seems to not only pose a threat to the internal functioning of tribal nations, but also provides some interesting opportunities for tribal survival, if the positive aspects of this dynamic process can be harnessed.

Populism seems to arise when prolonged economic uncertainty and seemingly unequal opportunities appear under regimes, especially where "transparency" is perceived by the people as lacking. Populism is defined as the rise of politically active sectors of common people, the "folk," as one scholar calls them,(13) who perceive that government and the economic structure is controlled by a privileged elite. While the concept arises from analyses of American and European democratic systems and is applied to cyclic changes in large systems of purportedly democratic government, it appears that this dynamic process could well apply to movements among tribal communities, as well.

Descriptions of populist movements show that they are not restricted to right-wing or left-wing policies, but are rather easily channeled by leadership that can identify themselves with the perceived economic injuries suffered by the righteous folk and articulate demands for fairness in the distribution of economic benefits within a society. Sometimes, self-aggrandizing leaders find easily isolated scapegoats as those responsible for the suffering of the folk, and propose simplistic solutions in emotional appeals that can create hysterical responses among those who feel threatened by the status quo. Those appeals can sometimes circulate among the folk and attract more people to the now emotionally charged movement, whose adherents become more and more resistant to reason in the rush to act quickly to end the perceived threat to the folk. The movement that results is a dynamo at this point, one which seems to take on a life of its own, often moving its adherents to political action outside the normal channels of government. One may notice, of course, that any movement among people is subject to some of these tendencies and that not all populist movements follow the seemingly mindless denial of reasoned dialogue and chauvinism that sometimes results when populist actions take an ugly turn. Some scholars think that while populist movements can eventually result in positive corrective innovations within democratic systems, leadership that arises in this cycle is crucial to the overall level of destructive outcomes. It is a dynamic, sometimes rapid process that certainly creates a situation where demagoguery can become rampant, revealing some of the more troubling aspects of human nature and group behaviors.

One needs to take special care when applying such analytical terminology as populism to the internal politics of Native nations, since the history of colonialism has required resistant strategies among Native people for many generations. Yet the observable elements of populism seem present across Native America and among other indigenous peoples, especially in the informal arena of public dialogue and debate. In Oneida and elsewhere across Native America, research into a tribe's traumatic experiences with policies of oppression and cultural and social assimilation, and such group movements as populism, may be helpful in evaluating the roots and possible solution to intratribal schisms.

A suggestion that might be fruitful in this research might include study of attitudes and backgrounds of tribal members in the processes a long-range project, such as has emerged in the Sustain Oneida(14) project of the Oneida Nation's Trust and Enrollment Office, which includes meetings and appeals for online responses from tribal members. The initiative is intended to gather opinions and begin an intratribal discussion about the tribe's looming problem of membership under the tribe's current constitution. Blood quantum requirements will soon, in the next two generations some say, cause the end of tribal membership, since intermarriage with other tribes and with non-Indian people steadily reduces the quantum of Oneida of Wisconsin genetics in each generation. Unless some form of eugenics us instituted, an unimaginable course of action, the tribal community of this generation will have to modify blood quantum requirements if the tribal nation is to survive. This is a sci-fi sort of situation taking place right now. Interestingly, the Sustain Oneida project has described this looming problem in the Kalihwisaks and on the tribal webpage in very provocative terms, asking for interested people to help define some very challenging courses of action.

Maybe the blood quantum issue isn't an identity issue after all. If the blood quantum concept were removed as a requirement of tribal citizenship, wouldn't you still be Oneida? It seems our identity is rooted in the same place as our sovereignty. Whatever new definition we develop of what it means to be Oneida should support and strengthen the concepts of our sovereignty.(15)

It is a call to Oneidas to consider their own identities and the identities of their descendants into the future, raising the possibility that a new solidarity might arise in this process of averting a very serious threat to tribal survival. Perhaps such projects as Sustain Oneida, that occur in the course tribal development, will help resolve some of the issues that disaffected tribal members now face if they are willing to help resolve difficult issues such as this one.

As we watch the threats to tribal unity mount from frequent divisive obstruction and self-serving ranting now so common in dialogue on tribal issue we can ask ourselves: Can Oneidas and the members of other tribal peoples find approaches to resolving the problems of confused perspectives that can result from the conflicting paradigms of tribalism and mass society? What can be done to regenerate what many believe were the once cohesive, egalitarian communities tribal peoples enjoyed long ago? Is our tribal memory of such conditions accurate or have we always dealt with factionalism and the desire for individual aggrandizement as elements of human nature? If so, can we find in structures in traditions of the Gayeneshagowa, or the Kayanla Kówa as the Oneidas say it, that helped minimize these human tendencies and somehow encourage people to seek the common good? If we do have traditions and identity-reinforcing values among us we can rely upon at this precarious moment in our peoples' histories, can we make use of those values to re-instill confidence in community relations and accountability in our tribal governments? Or are we ready to allow ourselves to be terminated or allow "mob rule" to destroy any hopes of effective community development and tribal governance? Clearly, answering these questions will take some personal commitment from us all if we hope to maintain any sense of ourselves as peoples into the future. After thousands of years, the crisis for this generation of Native people remains to renew the common identity we've always shared so that we work together to meet the many challenges we face as peoples.

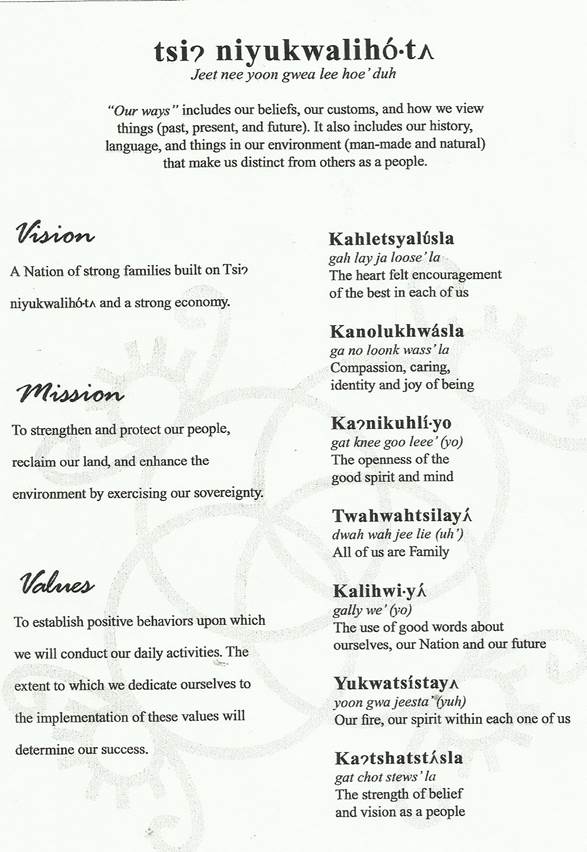

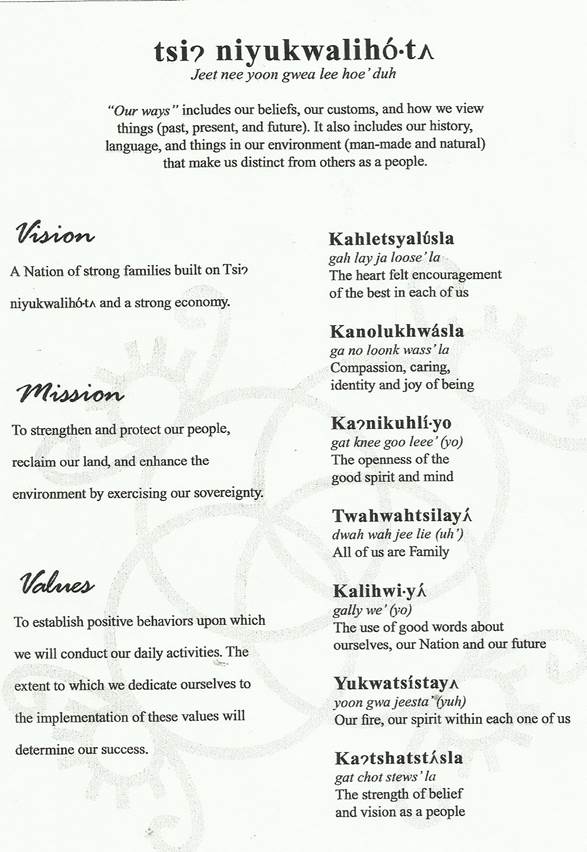

In Oneida, an on-going strategy to encourage civil discourse within the Oneida General Tribal Council is the printing of tribal language concepts in announcements and agendas prepared for their meetings. That approach places traditional values in compelling terms directly in the hands of GTC members at the very moment of participating in oral discussions that lead to voting. Recently, the following guidelines were published not only with the meeting materials, but in other venues like the Kalihwisaks and in many other publicly accessible locations.

Here is a copy of those values:

The values in this graphic are especially compelling for Oneida people, even though the tribal language is listed is "critically endangered" by UNESCO. In fact, for many, the concepts evoke an emotional response, one that can be very motivating for members of the General Tribal Council in its deliberations. One might hope that by keeping these values so close at hand during meetings, members of the GTC who might wish to obstruct the day's business would reconsider, based upon the power of generations-long experience.

Traditional concepts and values are available from several sources and can be used to educate and provide social controls as part of the environment of discourse in intratribal dialogues on issues. The Haudenosaunee Gayaneshagowa, the Great Law of Peace, as many know it, and the Kali wi'o, the Good Word, are basic oral documents of Haudenosaunee and Oneida identity. When referring to those oral documents, Oneidas again evoke reverence for their shared rights and responsibilities as members of the nation. It should be noted, though, that since these powerful sources of Oneida identity were displaced as working guides of Oneida lifeways by assimilation and missionization policies, many Oneidas know them only as historic, albeit highly respected documents. Other systems have taken over the political and religious commitments of many. Still, Oneidas can benefit from learning more about these powerful guides for Oneida life, especially as the Long House continues to gain influence in the lives of tribal members. Since about 1980, the Long House has attracted participants across the nation, even those who also continue to regularly attend Christian services. One can hope that personal commitment to the values these many-generations-old understandings will help to improve the quality of dialogues among tribal members on the pressing issues they face as a people.

Since the 1970's in Oneida, the regeneration of the Long House, called a "religion" by some, engenders hope that many of the elements of tribalism that were dormant or lost during the years of assimilation policies can also be regenerated. Kinship structures, for instance, are vital to that system of beliefs and ceremonies that reinforce virtues of communal responsibility and offer some powerful solutions to the internal bickering that has become a problem in tribal policy debates. The entire range of tribal values documented in Thomas' description of tribalism are essential elements of the traditional spiritual beliefs of many tribes, of course, and as Oneidas become more aware of the opportunities to participate in the Long House, one can hope greater tribal unity and better attitudes about internal debate will result.

Another interesting development in Oneida that may help with internal relationships is the regeneration of the ka' lahse, or lacrosse, as the game has come to be known around the world. When played in its traditional surroundings, the game reinforces many of the values of meeting challenges on the field of play as upstanding Oneidas. When the game is played in a traditional way, it is thought to be played for the enjoyment of the Creator, giving it a spiritual nature that reinforces traditional identity.(16) Such athletic games that attract the interest of young people as players and other tribal members as fans can reinforce a significant set of virtues like teamwork, mutual support, informal interaction among generations, and sacrifice for the good of others. Oneida sports in general bring people together in elemental ways, making the tribe's on-going dedication to fitness and health a community-building character. Since the game as a tradition has always been important among the several Haudenosaunee communities that still survive in Canada and in what is now New York State, it is also one of several bridges to the greater Haudenosaunee complex of communities, including the three major Oneida ones, in North America. Teams from many tribal nations will compete in lacrosse in the World Indigenous Games this year in Toronto,(17) in fact. It is a powerful dynamo for intertribal and even interethnic interaction, as people around the world play versions of this powerful sport and a few other games that have traditional connections to indigenous peoples. It seems to be one of many compelling, symbolic tools in the Oneida Nation's kit for resolving the problems of divisiveness.

Finally, for the purposes of this paper, it is important for Oneida people interested in improving the nature of debate within the community to review tribal government communications policies. There has always been a need to "caucus" among members, apart from the possible interference that might come from non-members who always seem to have an axe to grind in the formulation of tribal policy and even in cultural and social development necessary for tribal self-determination. That interference may come from people who believe they are being helpful and encouraging, but the influence of outside models has always irked tribal people hoping to build internal capacities and the self-sufficiency of tribal institutions. Of course, strategic policy and economic information as well as personnel records, have been withheld from public disclosure for fear of interference in the tribe's sovereign rights, the need to protect tribal citizens from harassment, or loss of market position, in the case of economic ventures. The concern that outside forces will try to manipulate tribal members directly in ways that threaten tribal sovereignty is certainly a valid one, given the threats of nearby groups like the Town of Hobart with its support from the Citizens Equal Rights Alliance, a national lobbying group that advocates termination of tribal sovereignty and treaty-based rights in general.

Yet the broad membership, including Oneidas who don't live near the reservation, need information upon which to act with intelligence in their position as the sovereign people of the Oneida. The Oneida Business Committee has responded admirably to this need by not only providing reliable funding for its newspaper, the Kalihwisaks, but shielding it from undue influence by tribal government via some explicit editorial policies.(18) It has also created a cutting-edge webpage in order to provide specific information to tribal membership, with a "members only" link that is conscientiously kept up-to-date. Local meetings and even hearings in off-reservation locations, such as in Milwaukee, have helped tribal members participate meaningfully as members of the sovereign nation. Tribal government has worked hard on this issue, but a review of how information is classified that educates tribal members who advocate greater transparency might help those members understand the need for security on some information, while reminding tribal information managers of their responsibility of finding efficient was to inform membership meaningfully about tribal issues. Communications media present an on-going challenge for tribal government in the self-determination era, one that needs continuous attention. While most tribal members seem satisfied with the transparency they experience within tribal government, a concerted effort to satisfy those members not happy with the quality of information they receive may help with internal debates on inherently controversial issues.

The author hopes this essay will be helpful as people evaluate the problems of divisive dialogues among tribal members involved in policy debates. In calling for reliance upon the wisdom available from tribal history and within tribal traditions, it may not offer much beyond the realization that in resolving internal issues, it is probably best to search first among a tribal nation's experiences for solutions. Many "conflict resolution" methods are available from outside sources, too, and should not automatically be rejected, but in the view of this author, finding solutions to this problem should help build the capacity of the community, relying upon people familiar with that history and committed to those traditions. Tribal scholars can help by providing the information necessary for important decisions based upon an emic, internal perspective. In the long run, though, a community-wide effort in resolving long-term internal conflicts must take place. That may seem like an obvious conclusion, but finding ways to engage the community in efforts that result in consensus over the rules of debate will take genius of the kind our ancestors were able to summon. It seems to demand a spiritual approach, one which can reach across generations to engage the group consciousness of the People.

Though one must admit that factionalism among Oneidas is not likely to disappear soon, the basis for reaching consensus in tribal internal dialogue is emerging, in the opinion of this optimistic author. The many aspects of Onu yote a'ka identity and the strategies already being implemented for building strong community values would seem to warrant the conclusion that it is only a matter of time before the respect necessary for overcoming discord among tribal members will emerge. The environment for consensus processes to take place is strengthening even as some individuals may not wish to end the divisiveness. Resolving the specific issues that have caused disaffection for some Oneidas will probably be necessary, where that can be done. As Vine Deloria, Jr. and Clifford Lytle did in their book The Nations Within: The Past and Future of Tribal Sovereignty as they made some potent recommendations for development of tribal communities back in 1984, "...these recommendations will identify problem areas and suggest possible alternatives that might be considered, providing the consideration is done in good faith by people determined to find a solution to pressing problems."(19) Perhaps this author's observations can also be part of that effort among Oneidas themselves, so long as they proceed in good faith with great determination in their quest to creatively draw upon the experiences and traditions that are the roots of their identity. It will take personal responsibility and community consciousness, of course. The rights of the individual will have to continually be re-balanced with the responsibilities to the community and to the spiritual and natural environment. Such values must always be foremost in the clear, rational thinking of the People! One can hope that as internal dialogues improve, and the People aspire more diligently to end abuse among ourselves, the abuse of other beings and forces that provide for human survival will also come under greater scrutiny. That is not a utopian dream, but a practical goal to strive for. It is a goal that will require excellent communications among people determined to find a consensus on how to proceed effectively in policy debates.

Author's statement: This brief research essay in not intended to be an exhaustive research project. Instead, is it written as support for a round table discussion and is an informal writing for discussion purposes in a conversational character. Readers are encouraged to conduct their own research on the topics raised in this paper. The round table is entitled "Returning the People to the Circle: A Roundtable Discussion on Overcoming the Fracturing of Indian Communities," moderated by Stephen M. Sachs. American Indian Studies Section, Western Social Sciences Association 59 th Annual Conference. Hyatt Regency Embarcadero Hotel, San Francisco, CA. April 13, 2017.

2 Vine Deloria, Jr. and Clifford M. Lytle, The Nations Within: The Past and Future of American Indian Sovereignty. Austin: U of TX Press, 1984, p. 247.

3 Deloria, Lytle, 247.

4 The concept of "peoplehood" has been explored by many scholars. This author's first scholarly exposure to that term was from Robert K. Thomas. "Mental Health: American Indian Tribal Societies," In American Indian Families: Development Strategies and Community Health, ed. Wayne Mitchell. Tempe: American Projects, Arizona State University, 1982, p. 1-16.

5 For more on this concept, see Eduardo Duran, Healing the Soul Wound: Counseling with American Indians and Other Native Peoples . New York: Teachers College Press, 2006.

6 Robert K. Thomas, "Mental Health: American Indian Tribal Societies," In American Indian Families: Development Strategies and Community Health, ed. Wayne Mitchell. Tempe: American Projects, Arizona State University, 1982, p. 1-16. Extensively elaborated upon in Richard M. Wheelock, "Indian Self-Determination: Implications for Tribal Communications Policies." Unpubl. PhD Diss. American Studies, University of New Mexico, Dec. 1995, p. 59-64.

7 Shearon A. Lowery and Melvin L. De Fleur, Milestones in Mass Communication Research: Media Effects. New York: Longman, 1983, p. 4-11.

8 Jack Campisi and Laurence M. Hauptman, eds. The Oneida Indian Experience: Two Perspectives. Syracuse: Syracuse U. Press, 1988.

9 For information on these tribal initiatives for learning tribal history, see <https://www.facebook.com/OneidaHistory/>

10 Constitution and By-Laws for the Oneida Tribal of Indians of Wisconsin. Approved 21 Dec. 1936. U.S. Dept. of the Interior, Off. of Indian Affairs. U.S. Govt. Printing Office, Washington, DC. Printed 1937.

11 The WPA collection and many subsequent documents concerning Oneida Language preservation may be found at "Wisconsin Oneida Language Preservation Project," Univ. of Wisconsin – Madison Libraries. https://uwdc.library.wisc.edu/collections/Oneida/ . Accessed 4 April, 2017

12 Though some have credited the Great Law of Peace as an important source of "representative" forms, Seneca scholar John Mohawk emphasized that "direct" democracy is a more accurate designation. See John Mohawk, "Thoughts of Peace: The Great Law" in Thinking in Indian: A John Mohawk Reader. Jose, Barreiro, ed. Golden, CO: Fulcrum Publishing, 2010., p. 243.

13 Cas Mudde, "The Populist Zeitgeist," Government and Opposition: International Journal of Comparative Politics. 27 Sept. 2004. Vol 39, Iss. 4, Autumn, 2004. P. 541-563.

14 "Sustain Oneida," Oneida Tribe of Indians of Wisconsin Webpage. https://uwdc.library.wisc.edu/collections/Oneida/ , accessed 7 Apr., 2017.

15 Oneida Trust and Enrollment Committee, "Whose House Do You Belong To?" Sustain Oneida project. https://oneida-nsn.gov/resources/enrollments/sustain-oneida/#The-IssueCrisis , Accessed 8 Apr., 2017.

16 The game was played in the creation story of the Oneida. See Amos Christjohn, "Creation Story," Oneida Nation of Wisconsin. Webpage. https://oneida-nsn.gov/our-ways/our-story/creation-story/#Shakohlewtha . Accessed 9 Apr., 2017.

17 North American Indigenous Games, July 16-23, 2017. "Past, Present, Future, All One." Aviva Center, Toronto. North American Indigenous Games Council.

18 The Kalihwisaks has published these policies in a very public way several times in recent years. An example of the two full-page, detailed publication of the policies is "Kalihwisaks Updated Policies and Procedures," Kalihwisaks, 12 Dec. 2013. Pp 11A-12A.

19 Deloria, Lytle, p. 248.